Pitt Epidemiologists Explore Trends in U.S. Beer Consumption

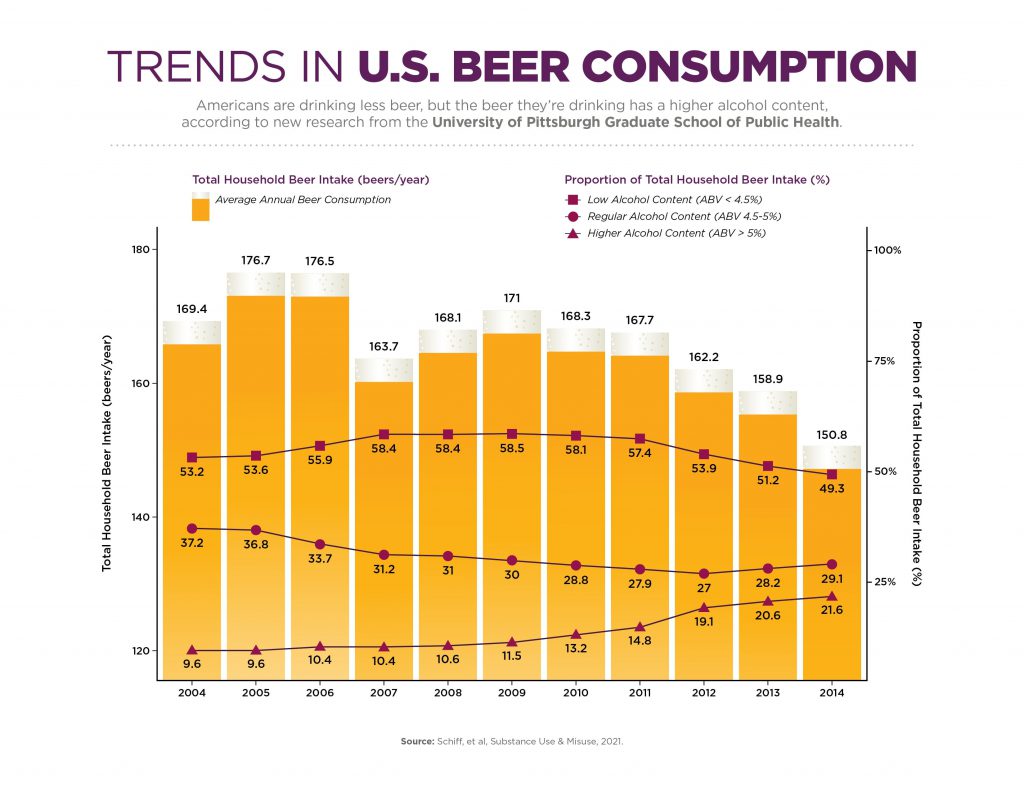

Americans are consuming more craft beer with higher alcohol content but are drinking less beer by volume, according to a new analysis led by epidemiologists at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

The study, published online and in a coming issue of the journal Substance Use & Misuse, looked at beer purchased in stores between 2004 and 2014. This is the first study to examine trends not only in the volume of beer purchased, but also the “beer specific” alcohol content.

“With the rise in popularity of craft breweries and the acquisition of such breweries by large-scale industry and investment companies, we’ve seen steady growth in consumption of higher alcohol content beer,” said senior author Anthony Fabio, Ph.D., M.P.H., associate professor of epidemiology at Pitt Public Health. “It is important that public health messaging include an emphasis on knowing the alcohol content of beer, not just the number of beers consumed, to ensure healthy alcohol consumption.”

The research team obtained data from the 2004-2014 Nielsen Consumer Panel, which is an annual survey of about 35,000 to 60,000 American households with information on purchasing. Researchers then meticulously matched the types of beer purchased with their alcohol content, grouping beers with 4.5% or less alcohol as “lower alcohol content” beers; with 4.5-5% alcohol as “regular” and beers with greater than 5% as “higher alcohol content.”

They found that in 2004, 9.6% of household beer consumed was of higher alcohol content; in 2014, that grew to 21.6%. Meanwhile, the number of 12-ounce beers each household purchased annually decreased from 169.4 in 2004 to 150.8 in 2014.

“We were pleasantly surprised to learn that—at least in terms of household beer consumption—Americans seem to be self-regulating. Households are buying higher alcohol content beer, but drinking less beer overall,” said lead author Mary Schiff, M.P.H., graduate student in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Epidemiology.

“We were pleasantly surprised to learn that—at least in terms of household beer consumption—Americans seem to be self-regulating. Households are buying higher alcohol content beer, but drinking less beer overall,” said lead author Mary Schiff, M.P.H., graduate student in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Epidemiology.

Federal health authorities have long addressed the importance of understanding the amount of alcohol in a “standard drink.” Different types of beer have very different amounts of alcohol content, and the amount of liquid in a glass, can or bottle does not tell how much alcohol is actually in a drink.

“That’s why it’s important to know how many standard drinks you consume,” Schiff said. “In the U.S., one ‘standard’ drink contains roughly 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is found in 12 ounces of regular, 5% alcohol beer. With the introduction of these higher alcohol content beers into the marketplace, this rule of thumb no longer holds as beers can be 8% or more alcohol. So, four bottles of regular beer equals four drinks, but four bottles of an India Pale Ale could be six-and-a-half regular beers.”

The research team couldn’t determine in this study if their findings translate to bars and restaurants. It’s possible that people are able to look at labels and determine the alcohol content of beer they purchase from the store or distributor, but that may be more difficult to do when the beer is served in a pint glass.

Consumption of higher-alcohol content beer grew notably starting in 2011, while lower-alcohol content beer consumption declined. This was when large-scale acquisition of craft breweries ramped up. For example, only 16 such acquisitions occurred in the 21 years from 1988 to 2010, yet in a quarter of that time, 20 acquisitions occurred between 2010 and 2014.

“During that time, Americans also shifted toward wine and spirits, and may have been drinking less beer for that reason,” said Fabio. “We didn’t examine purchases of alcoholic beverages other than beer, but national reports show steady increases in wine consumption.”

Finally, the research team found that more beer consumption was associated with being white, lower-income and of lower educational attainment, all consistent with previous studies.

Additional authors on this research are Dara Mendez, Ph.D., M.P.H., Tiffany L. Gary-Webb, Ph.D., M.H.S., and J. Jeffrey Inman, Ph.D., M.B.A., all of Pitt.

This research was funded in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant T32 HL083825. While NielsenIQ data was used in this analysis, NielsenIQ is not responsible for, had no role in and was not involved in analyzing and preparing the results of the study.